Buscar este blog

viernes, 15 de febrero de 2019

By Alex Nowrasteh and Andrew Forrester

Note: Years covered by this survey question: 2014.

Note: Years covered by this survey question: 2014.

Figure 3 asks respondents to agree or disagree with this statement: “I am often less proud of America than I would like to be.” In contrast to figures 1 and 2, those who agree with the statement here are less patriotic and those who disagree are more patriotic. Thirty-two percent of all immigrants and 33 percent of citizen immigrants agree with the statement compared to 37 percent of native-born Americans. Forty percent of all immigrants disagree with the statement that they are “often less proud of America,” slightly below the 42 percent of native-born Americans. Fifty-three percent of immigrants who are American citizens disagree. The responses of all immigrants and natives are not different to a statistically significant extent. Table 3 shows that the second generation are the least likely to be “less proud of America.” As a twist, they are also the most likely to answer “neither” and the least likely to disagree.

Figure 4 shows responses to the question, “How proud are you of America in each of the following? Its fair and equal treatment of all groups in society.” All immigrants are proudest of fair and equal treatment, with 23 percent of them saying they are very proud and 48 percent saying they are somewhat proud. Twenty-two percent of citizen immigrants say they are very proud and 42 percent say they are proud. Native-born Americans are the least proud of how America treats groups equally. Immigrant pride in how America treats groups equally is higher than that of native-born Americans.

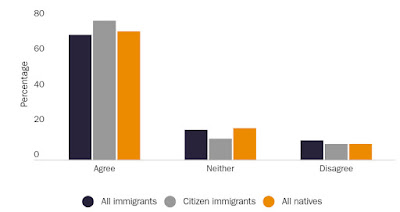

Figure 6 includes responses to the question, “How much do you agree or disagree with the following statement? The world would be a better place if people from other countries were more like the Americans.” This is just a general question that is correlated with how much the respondent likes Americans relative to foreigners. Thirty-nine percent of all immigrants and 40 percent of immigrant citizens agree that the world would be better if people from other countries were more like Americans. All immigrants are as likely as natives to disagree with the statement, while citizen immigrants are slightly more likely to disagree. However, there are no statistically significant differences between the responses of native-born Americans and all immigrants to this question. Table 6 shows that the second generation is more likely to say that “the world would be better if people from other countries were more like Americans” than any other generation of native-born Americans, as well as less likely to say the opposite.

There are at least three possible explanations for why immigrants are as patriotic or more patriotic than native-born Americans and why their love for this country is passed to the second generation. The first is that immigrants are more patriotic because they chose to become Americans. All things being equal, we should expect those who choose to become Americans to like America more than do those of us who were born here. Their children also understand that choice, which potentially explains their patriotic opinions. The second is that immigrants and their children have memories of how bad other countries are, so they are more appreciative of the United States and thus more patriotic. The third explanation, related to the second, is that disillusionment with the United States takes generations to set in, so only those whose ancestors settled here several generations ago are knowledgeable enough to be less patriotic. Regardless of the possible explanations, immigrants and their children are at least as patriotic as native-born Americans and frequently more so.

To a statistically significant extent, all immigrants are more likely to have a great deal of confidence in Congress, the presidency, and the Supreme Court than are native-born Americans (Table A3). Immigrants are also more likely to have only some confidence in Congress and the presidency, to a statistically significant extent, relative to natives. However, immigrants are less likely, to a statistically significant extent, to have confidence in the Supreme Court relative to natives-although the difference is the smallest of any coefficient reported. Immigrants are also less likely to have hardly any confidence in all three branches of government, relative to natives, to a statistically significant extent.

There are at least two possible explanations for the greater immigrant trust in the three branches of the federal government. The optimistic explanation is that immigrants appreciate how well the US government functions because they remember that their home governments were quite bad.10 The cynical explanation is that immigrants and their children have not had enough experience to realize how poorly these American branches of government function and hence it takes several generations of distance from the governments that their ancestors lived under to lose that perspective.

jueves, 14 de febrero de 2019

Ocho familias están demandando al Gobierno de Estados Unidos por el trauma provocado por la “inexplicable crueldad” de las separaciones familiares derivadas de la política inmigratoria de “tolerancia cero” impuesta por el presidente Donald Trump.

Los abogados de las familias sostienen que dicha política provocó severas secuelas emocionales y alteraciones en el comportamiento de los menores, incluyendo dificultades para dormir y para comer. La demanda se propone obtener una indemnización de tres millones de dólares por daños para cada familia.

El Gobierno estadounidense admitió haber separado a 2.700 menores de sus familias, pero un informe del Departamento de Salud y Servicios Humanos sugiere que podría haber miles más. La Casa de Anunciación, una agrupación sin fines de lucro con sede en la ciudad de El Paso, en el estado de Texas, afirmó recientemente al periódico The Guardian que la institución aún recibe llamados todas las semanas sobre nuevos casos de separaciones familiares.

Lo mas grave de esta política es que "Se desconoce el número total de niños separados por las autoridades migratorias de sus padres o de sus guardianes", Esa es la conclusión a la que llegó el inspector general del Departamento de Salud y Servicios Humanos, quien afirmó el jueves en un informe que los esfuerzos por registrar a esos niños han sido tan irregulares que se desconoce el número exacto de familias de migrantes que fueron separadas, y lo mas grave del asunto es que miles de niños podrían haber sido separados desde el año 2017, mucho antes de implementar la política de tolerancia cero, lo mas preocupante no se sabe cuantos ni donde están.

Fuente: www.democracynow.org - YouTube RT en Español

http://www.inmigracionyvisas.com/a4014-familias-demandan-a-Estados-Unidos-por-separacion-de-familias.html

miércoles, 13 de febrero de 2019

myE-Verify Sistema Gratuito Para Trabajadores Y Para Quienes Buscan Empleo En Estados Unidos

myE-Verify es un servicio gratis basado en el internet que tiene algo de interés para todas las personas que trabajan o están en busca de empleo en los Estados Unidos. E-Verify es para los empleadores; myE-Verify es para los trabajadores y para las personas en busca de empleo.

Casi 600,000 empleadores en más de 1.9 millones de sitios de contratación utilizan E-Verify para confirmar rápidamente la elegibilidad de empleo de los nuevos empleados. myE-Verify le ayuda a prepararse para un empleador que usa el sistema E-Verify. Para ello, le proporciona información sobre sus derechos y las responsabilidades del empleador. También le proporciona herramientas gratis para participar en el proceso y proteger su identidad.

Esto es lo que myE-Verify tiene para usted:

Self Check: Verifique su información personal contra los mismos registros que revisa E-Verify. Las personas en busca de trabajo pueden confirmar que sus registros están en orden o, si hay alguna discrepancia, reciben información sobre cómo actualizar sus datos.

Centro de Recursos: Materiales de información y aprendizaje desde la perspectiva del trabajador, sobre E-Verify y los procesos de verificación de elegibilidad de empleo, incluidos sus derechos, sus deberes, las responsabilidades de su empleador y la confidencialidad de su información. La información está disponible en texto y video. Muchos recursos están disponibles en varios idiomas.

Seguimiento de caso: De seguimiento al el estatus de su caso E-Verify en curso e infórmese si necesita hacer algo.

Cuentas personales myE-Verify: Cree su propia cuenta personal para tener acceso a las funciones adicionales de myE-Verify. Las personas que crean una cuentas tienen acceso a las siguientes dos funciones:

- Self Lock: Proteja su identidad e impida el uso no autorizado de su número de Seguro Social en E-Verify y Self Check. Self Lock está disponible para todos los que tienen una cuenta myE-Verify.

- Historial de caso: Por razones de seguridad e interés personal, vea dónde y cuándo se ha usado su información en E-Verify y Self Check.

Beneficios de myE-Verify

Cada herramienta y servicio en myE-Verify es absolutamente gratis. myE-Verify le permite confirmar que sus registros de elegibilidad de empleo son correctos, lo cual le da confianza en su búsqueda de trabajo. También le ayuda a proteger su identidad y le informa sobre las responsabilidades del empleador y sus derechos en el proceso de verificación de elegibilidad de empleo de E-Verify.

El Servicio de Ciudadanía e Inmigración de Estados Unidos (USCIS) desarrolló myE-Verify en respuesta a la solicitud del Congreso de ofrecer servicios a los trabajadores de los Estados Unidos para interactuar con el USCIS y participar en el proceso de E-Verify un programa del Departamento de Seguridad Nacional administrado por USCIS en conjunto con la Administración del Seguro Social.

Crear Una Cuenta

Para aprovechar algunas de las funciones que ofrece myE-Verify, debe crear una cuenta segura. Tiene que haber iniciado una sesión en su cuenta para usar las funciones de Self Lock e Historial de caso.

El primer paso es completar el proceso de Self Check y recibir una respuesta de "Autorización de empleo confirmada." Enseguida completará estos cuatros pasos para crear una cuenta myE-Verify:

1. Ingrese su información personal y cree un nombre de usuario y una contraseña.

2. Seleccione las preguntas de seguridad que se utilizarán para verificar su identidad si perdiera acceso a su cuenta.

3. Verifique que tiene acceso a una dirección de correo electrónico y a un número de teléfono.

4. Pase una prueba pequeña para verificar su identidad (similar a la prueba que tomó en Self Check).

Seguridad

myE-Verify se preocupa de su confidencialidad, y se adhiere al nivel 3 de aseguramiento del Instituto Nacional de Normas y Tecnología (NIST, por sus siglas en inglés) para confirmar su identidad. Para proteger su confidencialidad y garantizar la seguridad de su cuenta, el proceso de creación de una cuenta tiene varios pasos importantes. El proceso toma de 5 a 10 minutos en completarse.

Cuando cree su cuenta, debe completar una prueba pequeña para verificar su identidad. Las preguntas exactas que se generan serán únicas para usted y podrían incluir:

- Dirección

- El estado que emitió su número de Seguro Social (SSN)

- Los cuatro últimos dígitos de su número de Seguro Social

- Número de teléfono

- Empleador

- Información de su núcleo familiar

- Propiedad personal

- Número de licencia de conductor

- Preguntas sobre su historial crediticio en relación con préstamos hipotecarios, préstamo para compra de automóvil, préstamo personal, préstamo y crédito para estudiante

Para mantener este nivel de seguridad, completará un proceso de verificación de dos pasos cada vez que ingrese al sistema. Debe proveer exitosamente su nombre de usuario y contraseña antes de ingresar un código único que recibirá vía e-mail, texto o mensaje de voz.

En lugar de su nombre de usuario, podrá elegir la dirección de correo electrónico que proporcionó cuando creó su cuenta. Si olvida su contraseña, podrá usar las preguntas de seguridad que creó para ingresar al sistema y restablecer su contraseña.

Después de ingresar a su cuenta, podrá manejar sus preguntas de seguridad, restablecer su contraseña y actualizar su dirección de correo electrónico y número de teléfono. También tendrá acceso a las funciones de Self Lock e Historial de caso. Self Lock le permite manejar el uso de su número de Seguro Social en E-Verify y Self Check para evitar el uso fraudulento de su identidad relacionado con el empleo. La función de Historial de caso le permite ver cuándo se usó su información personal en Self Check y en E-Verify, lo que agrega más transparencia a E-Verify y protección de identidad a los empleados y las personas en busca de trabajo.

Suscríbase aquí a myE-Verify para recibir actualizaciones por correo electrónico.

Fuente: www.e-verify.gov

http://www.inmigracionyvisas.com/a3171-E-Verify-en-espanol.html

martes, 12 de febrero de 2019

U.S. immigration law is very complex, and there is much confusion as to how it works. The Immigration and Naturalization Act (INA), the body of law governing current immigration policy, provides for an annual worldwide limit of 675,000 permanent immigrants, with certain exceptions for close family members. Lawful permanent residency allows a foreign national to work and live lawfully and permanently in the United States. Lawful permanent residents (LPRs) are eligible to apply for nearly all jobs (i.e., jobs not legitimately restricted to U.S. citizens) and can remain in the country even if they are unemployed. Each year the United States also admits noncitizens on a temporary basis. Annually, Congress and the President determine a separate number for refugee admissions.

Immigration to the United States is based upon the following principles: the reunification of families, admitting immigrants with skills that are valuable to the U.S. economy, protecting refugees, and promoting diversity. This fact sheet provides basic information about how the U.S. legal immigration system is designed.

I. Family-Based Immigration

Family unification is an important principle governing immigration policy. The family-based immigration category allows U.S. citizens and LPRs to bring certain family members to the United States. Family-based immigrants are admitted either as immediate relatives of U.S. citizens or through the family preference system.

Prospective immigrants under the immediate relatives’ category must meet standard eligibility criteria, and petitioners must meet certain age and financial requirements. Immediate relatives are:

- spouses of U.S. citizens;

- unmarried minor children of U.S. citizens (under 21-years-old);

- parents of U.S. citizens (petitioner must be at least 21-years-old to petition for a parent).

A limited number of visas are available every year under the family preference system, but prospective immigrants must meet standard eligibility criteria, and petitioners must meet certain age and financial requirements. The preference system includes:

- adult children (married and unmarried) and brothers and sisters of U.S. citizens (petitioner must be at least 21-years-old to petition for a sibling),

- spouses and unmarried children (minor and adult) of LPRs.

In order to balance the overall number of immigrants arriving based on family relationships, Congress established a complicated system for calculating the available number of family preference visas for any given year. The number is determined by starting with 480,000 and then subtracting the number of immediate relative visas issued during the previous year and the number of aliens “paroled” into the U.S. during the previous year. Any unused employment preference immigrant numbers from the preceding year are then added to this sum to establish the number of visas that remain for allocation through the preference system. However, by law, the number of family-based visas allocated through the preference system may not be lower than 226,000. In reality, due to large numbers of immediate relatives, the actual number of preference system visas available each year has been 226,000. Consequently, the total number of family-based visas often exceeds 480,000.

In Fiscal Year (FY) 2014, family-based immigrants comprised 64 percent of all new LPRs in the United States.

The family-based immigration system is summarized in Table 1.

In order to be admitted through the family-based immigration system, a U.S. citizen or LPR sponsor must petition for an individual relative, establish the legitimacy of the relationship, meet minimum income requirements, and sign an affidavit of support stating that the sponsor will be financially responsible for the family member(s) upon arrival in the United States.

The spouses and children who accompany or follow the principal immigrants (those who qualify as immediate relatives or in family-preference categories) are referred to as derivative immigrants. The number of visas granted to derivative immigrants is counted under the appropriate category limits. For example, in FY 2013, 65,536 people were admitted as siblings of U.S. citizens; 27,022 were actual siblings of U.S. citizens (the principal immigrants); 14,891 were spouses of principal immigrants; and 23,623 were children of principal immigrants.

II. Employment-Based Immigration

The United States provides various ways for immigrants with valuable skills to come to the country on either a permanent or a temporary basis.

Temporary Visa Classifications

Temporary employment-based visa classifications permit employers to hire and petition for foreign nationals for specific jobs for limited periods. Most temporary workers must work for the employer that petitioned for them and have limited ability to change jobs. There are more than 20 types of visas for temporary nonimmigrant workers. These include L-1 visas for intracompany transfers; various P visas for athletes, entertainers, and skilled performers; R-1 visas for religious workers; various A visas for diplomatic employees; O-1 visas for workers of extraordinary ability; and various H visas for both highly-skilled and lesser-skilled employment. The visa classifications vary in terms of their eligibility requirements, duration, whether they permit workers to bring dependents, and other factors. In most cases, they must leave the United States if their status expires or if their employment is terminated.

Permanent Immigration

The overall numerical limit for permanent employment-based immigrants is 140,000 per year. This number includes the immigrants plus their eligible spouses and minor unmarried children, meaning the actual number of employment-based immigrants is less than 140,000 each year. The 140,000 visas are divided into five preference categories, detailed in Table 2.

In FY 2014, immigrants admitted through the employment preferences made up 15 percent of all new LPRs in the United States.

III. Per-Country Ceilings

In addition to the numerical limits placed upon the various immigration preferences, the INA also places a limit on how many immigrants can come to the United States from any one country. Currently, no group of permanent immigrants (family-based and employment-based) from a single country can exceed seven percent of the total amount of people immigrating to the United States in a single fiscal year. This is not a quota to ensure that certain nationalities make up seven percent of immigrants, but rather a limit that is set to prevent any immigrant group from dominating immigration patterns to the United States.

IV. Refugees and Asylees

Protection of Refugees, Asylees, and other Vulnerable Populations

There are several categories of legal admission available to people who are fleeing persecution or are unable to return to their homeland due to life-threatening or extraordinary conditions.

Refugees are admitted to the United States based upon an inability to return to their home countries because of a “well-founded fear of persecution” due to their race, membership in a particular social group, political opinion, religion, or national origin. Refugees apply for admission from outside of the United States, generally from a “transition country” that is outside their home country. The admission of refugees turns on numerous factors, such as the degree of risk they face, membership in a group that is of special concern to the United States (designated yearly by the President of the United States and Congress), and whether or not they have family members in the United States.

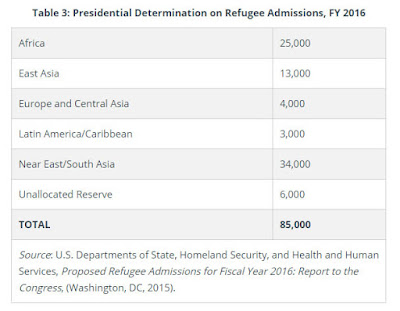

Each year the President, in consultation with Congress, determines the numerical ceiling for refugee admissions. The total limit is broken down into limits for each region of the world as well. After September 11, 2001, the number of refugees admitted into the United States fell drastically, but annual admissions have steadily increased as more sophisticated means of conducting security checks have been put into place.

For FY 2016, the President set the worldwide refugee ceiling at 85,000, shown in Table 3 with the regional allocations.

Asylum is available to persons already in the United States who are seeking protection based on the same five protected grounds upon which refugees rely. They may apply at a port of entry at the time they seek admission or within one year of arriving in the United States. There is no limit on the number of individuals who may be granted asylum in a given year nor are there specific categories for determining who may seek asylum. In FY 2014, 23,533 individuals were granted asylum.

Refugees and asylees are eligible to become LPRs one year after admission to the United States as a refugee or one year after receiving asylum.

V. The Diversity Visa Program

The Diversity Visa lottery was created by the Immigration Act of 1990 as a dedicated channel for immigrants from countries with low rates of immigration to the United States. Each year 55,000 visas are allocated randomly to nationals from countries that have sent less than 50,000 immigrants to the United States in the previous 5 years. Of the 55,000, up to 5,000 are made available for use under the NACARA program. This results in a reduction of the actual annual limit to 50,000.

Although originally intended to favor immigration from Ireland (during the first three years of the program at least 40 percent of the visas were exclusively allocated to Irish immigrants), the Diversity Visa program has become one of the only avenues for individuals from certain regions in the world to secure a green card.

To be eligible for a diversity visa, an immigrant must have a high-school education (or its equivalent) or have, within the past five years, a minimum of two years working in a profession requiring at least two years of training or experience. Spouses and minor unmarried children of the principal applicant may also enter as dependents. A computer-generated random lottery drawing chooses selectees for diversity visas. The visas are distributed among six geographic regions with a greater number of visas going to regions with lower rates of immigration, and with no visas going to nationals of countries sending more than 50,000 immigrants to the United States over the last five years.

People from eligible countries in different continents may register for the lottery. However, because these visas are distributed on a regional basis, the program especially benefits Africans and Eastern Europeans.

VI. Other Forms of Humanitarian Relief

Temporary Protected Status (TPS) is granted to people who are in the United States but cannot return to their home country because of “natural disaster,” “extraordinary temporary conditions,” or “ongoing armed conflict.” TPS is granted to a country for six, 12, or 18 months and can be extended beyond that if unsafe conditions in the country persist. TPS does not necessarily lead to LPR status or confer any other immigration status.

Deferred Enforced Departure (DED) provides protection from deportation for individuals whose home countries are unstable, therefore making return dangerous. Unlike TPS, which is authorized by statute, DED is at the discretion of the executive branch. DED does not necessarily lead to LPR status or confer any other immigration status.

Certain individuals may be allowed to enter the U.S. through parole, even though they may not meet the definition of a refugee and may not be eligible to immigrate through other channels. Parolees may be admitted temporarily for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.

VII. U.S. Citizenship

In order to qualify for U.S. citizenship through naturalization, an individual must have had LPR status (a green card) for at least five years (or three years if he or she obtained the green card through a U.S.-citizen spouse or through the Violence Against Women Act, VAWA). There are other exceptions including, but not limited to, members of the U.S. military who serve in a time of war or declared hostilities. Applicants for U.S. citizenship must be at least 18-years-old, demonstrate continuous residency, demonstrate “good moral character,” pass English and U.S. history and civics exams (with certain exceptions), and pay an application fee, among other requirements.

Source: www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org

http://www.inmigracionyvisas.com/a4013-United-States-Immigration-System.html

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)