Buscar este blog

Mostrando entradas con la etiqueta immigration system. Mostrar todas las entradas

Mostrando entradas con la etiqueta immigration system. Mostrar todas las entradas

viernes, 3 de mayo de 2019

Closing USCIS International Offices Will Leave US Citizens, Abroad Without Help

Written by Angelica Duron

lunes, 25 de marzo de 2019

Statement of Donald Kerwin, Executive Director of the Center for Migration Studies, on the US Border and Border Wall

The President Trump addressed the nation from the Oval Office, asserting that there exists a crisis on our southern border which necessitates the construction of a border wall.

Despite the president’s claims that a crisis exists on the border, the facts demonstrate otherwise. The Center for Migration Studies of New York (CMS) has released several reports which show that border crossings have dropped significantly over the past several years.

A 2016 CMS report showed that net migration from Mexico between 2010 and 2016 dropped 11 percent. The undocumented population from Mexico dropped by an additional 400,000 from 2016 to 2017. Migration from other parts of Latin America, save the Northern Triangle, also dropped significantly. The report’s overall conclusion was that the number of undocumented in the nation had dropped to 10.8 million, a new low. The report can be found at https://cmsny.org/publications/warren-undocumented-2016/

CMS also issued a report which found that the number of persons who have overstayed their visas between 2008 and 2014 had exceeded the number of border crossers. In 2014, overstays represented two-thirds of those who joined the undocumented population. The report can be found at https://cmsny.org/publications/jmhs-visa-overstays-border-wall/

A recent study by several immigrant rights organizations, entitled Death, Damage, and Failure: Past, Present, and Future Impacts of Walls on the US-Mexico Border, details the damage caused to border communities by already existing walls and fencing along the border, and how the extension of a wall would cause economic, environmental, and human harm moving forward.

The human tragedy at our border, where thousands of children and families are fleeing persecution and violence from the Northern Triangle countries of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, is where this administration and Congress should focus its attention.

A series of measures designed to deter these vulnerable populations from fleeing their countries, including family separation, mandatory detention, zero tolerance, and denial of entry at the border are undermining their legal and human rights, guaranteed under both domestic and international law. They are handing themselves over to Border Patrol agents in search of protection, not trying to enter the country illegally. The Administration and Congress should act to end these inhumane policies and provide protection to vulnerable women and children.

The real crisis exists in the Northern Triangle of Central America, where organized crime threatens residents with impunity and there exists a lack of stability and opportunity. Instead of appropriating nearly $5.7 billion for an ineffective and damaging wall, Congress and President Trump should use some portion of this funding to address the push factors causing flight from the region. Addressing root causes of flight is the most humane and effective solution to outward migration.

Instead of shutting down the government over a wall, President Trump and Congress also should enact a legislative package which provides permanent status to Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival (DACA) and Temporary Protected Status (TPS) recipients, immigrant populations who have built equities in our nation. CMS has issued studies on the contributions of each of these populations, which can be found at https://cmsny.org/publications/jmhs-potential-beneficiaries-of-daca-dapa/ and https://cmsny.org/publications/jmhs-tps-elsalvador-honduras-haiti/.

Our nation deserves an immigration system which protects human rights and human dignity while upholding the rule of law. This requires immigration reform which honors our values and traditions as a nation of immigrants. Building walls only divides us as a country and does not address the sources of global migration.

Fuente: www.cmsny.org/

https://www.inmigracionyvisas.com/a4074-border-crossings-have-dropped-over-the-past-several-years.html

martes, 12 de febrero de 2019

U.S. immigration law is very complex, and there is much confusion as to how it works. The Immigration and Naturalization Act (INA), the body of law governing current immigration policy, provides for an annual worldwide limit of 675,000 permanent immigrants, with certain exceptions for close family members. Lawful permanent residency allows a foreign national to work and live lawfully and permanently in the United States. Lawful permanent residents (LPRs) are eligible to apply for nearly all jobs (i.e., jobs not legitimately restricted to U.S. citizens) and can remain in the country even if they are unemployed. Each year the United States also admits noncitizens on a temporary basis. Annually, Congress and the President determine a separate number for refugee admissions.

Immigration to the United States is based upon the following principles: the reunification of families, admitting immigrants with skills that are valuable to the U.S. economy, protecting refugees, and promoting diversity. This fact sheet provides basic information about how the U.S. legal immigration system is designed.

I. Family-Based Immigration

Family unification is an important principle governing immigration policy. The family-based immigration category allows U.S. citizens and LPRs to bring certain family members to the United States. Family-based immigrants are admitted either as immediate relatives of U.S. citizens or through the family preference system.

Prospective immigrants under the immediate relatives’ category must meet standard eligibility criteria, and petitioners must meet certain age and financial requirements. Immediate relatives are:

- spouses of U.S. citizens;

- unmarried minor children of U.S. citizens (under 21-years-old);

- parents of U.S. citizens (petitioner must be at least 21-years-old to petition for a parent).

A limited number of visas are available every year under the family preference system, but prospective immigrants must meet standard eligibility criteria, and petitioners must meet certain age and financial requirements. The preference system includes:

- adult children (married and unmarried) and brothers and sisters of U.S. citizens (petitioner must be at least 21-years-old to petition for a sibling),

- spouses and unmarried children (minor and adult) of LPRs.

In order to balance the overall number of immigrants arriving based on family relationships, Congress established a complicated system for calculating the available number of family preference visas for any given year. The number is determined by starting with 480,000 and then subtracting the number of immediate relative visas issued during the previous year and the number of aliens “paroled” into the U.S. during the previous year. Any unused employment preference immigrant numbers from the preceding year are then added to this sum to establish the number of visas that remain for allocation through the preference system. However, by law, the number of family-based visas allocated through the preference system may not be lower than 226,000. In reality, due to large numbers of immediate relatives, the actual number of preference system visas available each year has been 226,000. Consequently, the total number of family-based visas often exceeds 480,000.

In Fiscal Year (FY) 2014, family-based immigrants comprised 64 percent of all new LPRs in the United States.

The family-based immigration system is summarized in Table 1.

In order to be admitted through the family-based immigration system, a U.S. citizen or LPR sponsor must petition for an individual relative, establish the legitimacy of the relationship, meet minimum income requirements, and sign an affidavit of support stating that the sponsor will be financially responsible for the family member(s) upon arrival in the United States.

The spouses and children who accompany or follow the principal immigrants (those who qualify as immediate relatives or in family-preference categories) are referred to as derivative immigrants. The number of visas granted to derivative immigrants is counted under the appropriate category limits. For example, in FY 2013, 65,536 people were admitted as siblings of U.S. citizens; 27,022 were actual siblings of U.S. citizens (the principal immigrants); 14,891 were spouses of principal immigrants; and 23,623 were children of principal immigrants.

II. Employment-Based Immigration

The United States provides various ways for immigrants with valuable skills to come to the country on either a permanent or a temporary basis.

Temporary Visa Classifications

Temporary employment-based visa classifications permit employers to hire and petition for foreign nationals for specific jobs for limited periods. Most temporary workers must work for the employer that petitioned for them and have limited ability to change jobs. There are more than 20 types of visas for temporary nonimmigrant workers. These include L-1 visas for intracompany transfers; various P visas for athletes, entertainers, and skilled performers; R-1 visas for religious workers; various A visas for diplomatic employees; O-1 visas for workers of extraordinary ability; and various H visas for both highly-skilled and lesser-skilled employment. The visa classifications vary in terms of their eligibility requirements, duration, whether they permit workers to bring dependents, and other factors. In most cases, they must leave the United States if their status expires or if their employment is terminated.

Permanent Immigration

The overall numerical limit for permanent employment-based immigrants is 140,000 per year. This number includes the immigrants plus their eligible spouses and minor unmarried children, meaning the actual number of employment-based immigrants is less than 140,000 each year. The 140,000 visas are divided into five preference categories, detailed in Table 2.

In FY 2014, immigrants admitted through the employment preferences made up 15 percent of all new LPRs in the United States.

III. Per-Country Ceilings

In addition to the numerical limits placed upon the various immigration preferences, the INA also places a limit on how many immigrants can come to the United States from any one country. Currently, no group of permanent immigrants (family-based and employment-based) from a single country can exceed seven percent of the total amount of people immigrating to the United States in a single fiscal year. This is not a quota to ensure that certain nationalities make up seven percent of immigrants, but rather a limit that is set to prevent any immigrant group from dominating immigration patterns to the United States.

IV. Refugees and Asylees

Protection of Refugees, Asylees, and other Vulnerable Populations

There are several categories of legal admission available to people who are fleeing persecution or are unable to return to their homeland due to life-threatening or extraordinary conditions.

Refugees are admitted to the United States based upon an inability to return to their home countries because of a “well-founded fear of persecution” due to their race, membership in a particular social group, political opinion, religion, or national origin. Refugees apply for admission from outside of the United States, generally from a “transition country” that is outside their home country. The admission of refugees turns on numerous factors, such as the degree of risk they face, membership in a group that is of special concern to the United States (designated yearly by the President of the United States and Congress), and whether or not they have family members in the United States.

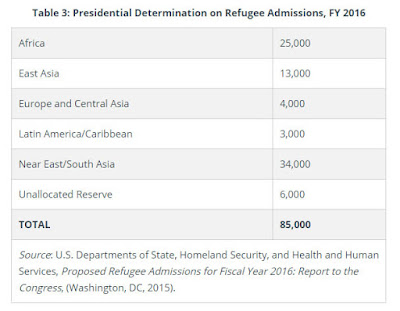

Each year the President, in consultation with Congress, determines the numerical ceiling for refugee admissions. The total limit is broken down into limits for each region of the world as well. After September 11, 2001, the number of refugees admitted into the United States fell drastically, but annual admissions have steadily increased as more sophisticated means of conducting security checks have been put into place.

For FY 2016, the President set the worldwide refugee ceiling at 85,000, shown in Table 3 with the regional allocations.

Asylum is available to persons already in the United States who are seeking protection based on the same five protected grounds upon which refugees rely. They may apply at a port of entry at the time they seek admission or within one year of arriving in the United States. There is no limit on the number of individuals who may be granted asylum in a given year nor are there specific categories for determining who may seek asylum. In FY 2014, 23,533 individuals were granted asylum.

Refugees and asylees are eligible to become LPRs one year after admission to the United States as a refugee or one year after receiving asylum.

V. The Diversity Visa Program

The Diversity Visa lottery was created by the Immigration Act of 1990 as a dedicated channel for immigrants from countries with low rates of immigration to the United States. Each year 55,000 visas are allocated randomly to nationals from countries that have sent less than 50,000 immigrants to the United States in the previous 5 years. Of the 55,000, up to 5,000 are made available for use under the NACARA program. This results in a reduction of the actual annual limit to 50,000.

Although originally intended to favor immigration from Ireland (during the first three years of the program at least 40 percent of the visas were exclusively allocated to Irish immigrants), the Diversity Visa program has become one of the only avenues for individuals from certain regions in the world to secure a green card.

To be eligible for a diversity visa, an immigrant must have a high-school education (or its equivalent) or have, within the past five years, a minimum of two years working in a profession requiring at least two years of training or experience. Spouses and minor unmarried children of the principal applicant may also enter as dependents. A computer-generated random lottery drawing chooses selectees for diversity visas. The visas are distributed among six geographic regions with a greater number of visas going to regions with lower rates of immigration, and with no visas going to nationals of countries sending more than 50,000 immigrants to the United States over the last five years.

People from eligible countries in different continents may register for the lottery. However, because these visas are distributed on a regional basis, the program especially benefits Africans and Eastern Europeans.

VI. Other Forms of Humanitarian Relief

Temporary Protected Status (TPS) is granted to people who are in the United States but cannot return to their home country because of “natural disaster,” “extraordinary temporary conditions,” or “ongoing armed conflict.” TPS is granted to a country for six, 12, or 18 months and can be extended beyond that if unsafe conditions in the country persist. TPS does not necessarily lead to LPR status or confer any other immigration status.

Deferred Enforced Departure (DED) provides protection from deportation for individuals whose home countries are unstable, therefore making return dangerous. Unlike TPS, which is authorized by statute, DED is at the discretion of the executive branch. DED does not necessarily lead to LPR status or confer any other immigration status.

Certain individuals may be allowed to enter the U.S. through parole, even though they may not meet the definition of a refugee and may not be eligible to immigrate through other channels. Parolees may be admitted temporarily for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.

VII. U.S. Citizenship

In order to qualify for U.S. citizenship through naturalization, an individual must have had LPR status (a green card) for at least five years (or three years if he or she obtained the green card through a U.S.-citizen spouse or through the Violence Against Women Act, VAWA). There are other exceptions including, but not limited to, members of the U.S. military who serve in a time of war or declared hostilities. Applicants for U.S. citizenship must be at least 18-years-old, demonstrate continuous residency, demonstrate “good moral character,” pass English and U.S. history and civics exams (with certain exceptions), and pay an application fee, among other requirements.

Source: www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org

http://www.inmigracionyvisas.com/a4013-United-States-Immigration-System.html

miércoles, 8 de marzo de 2017

Trump’s Immigration Remarks at Joint Address, Debunked

Written by Joshua Breisblatt in Border Enforcement, Enforcement, Executive Action, Interior Enforcement

This week, President Trump gave an address to a joint session of Congress where he continued his divisive, inaccurate rhetoric on immigration. Some analysts have said Trump moderated his tone in this speech, but in reality Trump isn’t shifting from his hard-line immigration policies. In his speech, he continued to falsely blaming immigrants for the underlying cause for many issues our country faces.

Below are five statements from President Trump’s Joint Address that need to be corrected and explained.

1. Trump claimed that we’ve left “our own borders wide open for anyone to cross.”

This is categorically false Since the last major overhaul of the U.S. immigration system in 1986, the federal government has spent an estimated $263 billion on immigration and border enforcement. Currently, the number of border and interior enforcement personnel stands at more than 49,000. The number of U.S. Border Patrol agents nearly doubled from Fiscal Year (FY) 2003 to FY 2016 with Border Patrol now required to have a record 21,370 agents. Additionally, the number of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents devoted to its office of Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) nearly tripled from FY 2003 to FY 2016.

2. Trump said that immigrants aren’t contributing to our economy and instead are “costing the country billions.”

Once again, Trump is incorrect. The study Trump cited and misconstrued was conducted by the National Academies of Sciences (NAS), Engineering, and Medicine. The same report flatly states found that immigrants have “little to no negative effects on the overall wages or employment of native-born workers in the long term.” The NAS study also finds that immigrant workers expand the size of the U.S. economy by an estimated 11 percent annually, which translates out to $2 trillion in 2016. Further, the children of immigrants were found to be the largest net fiscal contributors among any group, native or foreign-born, creating significant economic benefits for every American.

3. Trump said that the government is “removing gang members, drug dealers and criminals that threaten our communities and prey on our citizens.”

Despite the rhetoric, Trump has complicated immigration enforcement by making virtually all of the undocumented population a priority . The new administration is ignoring priorities that were put into place by the Obama Administration as a way to manage limited law enforcement resources and prioritize those who pose a threat to public safety and national security. The priorities recognized that there is a finite budget available for immigration enforcement, thus making prioritization important. The approach now being pursued by the Trump Administration casts a very wide net and will result in an aggressive and unforgiving approach to immigration enforcement moving forward.

4. Trump believes a merit-based immigration system will improve the economy.

The idea of a merit-based system is not new but it usually has been discussed as one piece to updating our immigration system, not the only piece as discussed in this speech. At its core, the allocation of points is not a neutral act, but instead reflects a political view regarding the “desired immigrant.” Since the enactment of the Immigration and Nationality Act in 1965, legal immigration to the United States has been based primarily on the family ties or the work skills of prospective immigrants.

The contributions of family-based immigrants to the U.S. economy, local communities, and the national fabric are many. They account for a significant portion of domestic economic growth, contribute to the well-being of the current and future labor force, play a key role in business development and community improvement, and are among the most upwardly mobile segments of the labor force. And if cutting family-based immigration becomes part of a trade-off for a merit-based system, we would be turning our back on a centuries’ old tradition of family members already in the United States supporting newcomer relatives by helping them get on their feet and facilitating their integration.

5. Trump attempted to make the link between immigrants and crime through his newly created office of Victims Of Immigration Crime Engagement (VOICE).

Despite the implications of this new office at DHS which seeks to demonize all immigrants, immigrants are actually less likely to commit serious crimes or be behind bars than the native-born. Additionally, high rates of immigration are associated with lower rates of violent crime and property crime. This holds true for both legal immigrants and the unauthorized, regardless of their country of origin or level of education.

Photo Courtesy of C-SPAN.

Source: http://immigrationimpact.com

http://inmigracionyvisas.com/a3556-Trump-Immigration-Remarks-at-Joint-Address.html

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)