Buscar este blog

Mostrando entradas con la etiqueta immigration courts. Mostrar todas las entradas

Mostrando entradas con la etiqueta immigration courts. Mostrar todas las entradas

miércoles, 31 de julio de 2019

The Institutional Hearing Program (IHP): An Overview

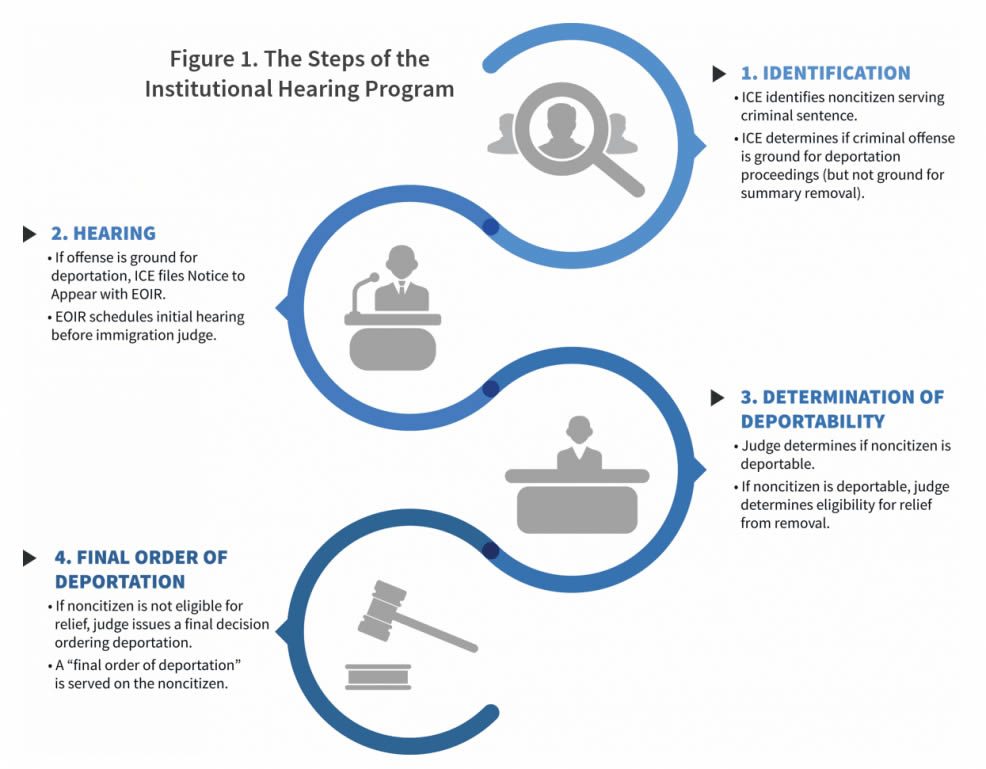

The Institutional Hearing Program (IHP) permits immigration judges to conduct removal proceedings for noncitizens serving criminal sentences in certain correctional facilities. Unfortunately, there is little reliable, publicly accessible information about how the IHP functions. Lack of information notwithstanding, a readily apparent problem with the IHP is that most noncitizens do not have access to attorneys who can represent them in their deportation hearings. Typically, these individuals fare much worse than those with an attorney.

lunes, 29 de julio de 2019

Appeals Court Decision Means Hundreds Of Migrants Were Unlawfully Convicted

By Emma Winger

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals issued a decision clarifying limits on when federal prosecutors can charge immigrants with illegal entry and reentry into the United States this week. Under this decision, it will be more difficult for the government to criminally charge immigrants who attempt to enter the United States outside a port of entry in order seek asylum. Hundreds of prior convictions are also now potentially invalid.

The Trump administration has prioritized the criminal prosecution of migrants who cross the U.S.-Mexico border without inspection – most infamously, as part of its “ zero tolerance” policy , where the administration used the criminal prosecution of parents as justification for separating those parents from their children.

As the administration has increased illegal entry prosecutions, it has simultaneously created new barriers for asylum-seekers attempting to lawfully enter the U.S., including turning migrants back from ports of entry and requiring asylum applicants towait in Mexico while immigration judges consider their asylum applications.

The misdemeanor law criminalizing illegal entry, often referred to as Section 1325 , covers three separate types of conduct: (1) entering or attempting to enter outside an official port of entry; (2) “eluding” inspection by immigration officers; and (3) entering through fraud. Federal prosecutors were charging migrants with “eluding” inspection – the second prong of Section 1325—in cases where the arrest took place far from a port of entry. The Ninth Circuit Court said prosecutors were wrong – that they can only charge a person with eluding inspection if they were arrested at or near a port of entry. Migrants who cross the border outside of a port of entry must be charged under the first prong of Section 1325 – otherwise, the first prong doesn’t serve any purpose.

This decision is significant because the law limits who can be charged under the first prong of Section 1325 for entering or attempting to enter outside a port of entry. To illegally “enter” the U.S. a person must cross the border and avoid detection by immigration authorities. A migrant who crosses the border and immediately turns herself over to immigration authorities in order to apply for asylum hasn’t unlawfully entered the U.S.

The Ninth Circuit decision means that many migrants, including parents separated from their children under the “zero tolerance” policy, were unlawfully charged with and convicted of eluding inspection. It further calls into question the government’s widespread practice of prosecuting those who seek refuge in this country, and brings the United States closer to compliance with its international obligations, which forbid prosecuting asylum seekers. No person fleeing violence in their home country should be criminally prosecuted for exercising their right to seek asylum.

Source: www.immigrationimpact.com

https://www.inmigracionyvisas.com/a4348-Hundreds-Of-Migrants-Were-Unlawfully-Convicted.html

lunes, 8 de julio de 2019

Certain Detained Asylum Seekers Must Receive a Bond Hearing Within 7 Days

Written by Kristin Macleod-Ball

Attorney General William Barr announced in April 2019 plans to eliminate bond hearings for immigrants who pass an asylum screening interview after entering the United States. This would have forced many people to remain incarcerated for months or years during their asylum proceedings. However, on Tuesday, a federal court recognized that this fundamental attack on due process is unconstitutional.

A U.S. district court judge found that the government cannot lock up certain detained asylum seekers without giving a bond hearing before an immigration judge. The Seattle judge ordered that those hearings must take place within seven days of requesting one and that immigration courts must provide new legal protections at the hearings.

This ruling comes after the Attorney General said, in a case called Matter of M-S-, that he would bar immigration courts from deciding whether to release certain asylum seekers held in immigration detention during their often-lengthy asylum proceedings.

The district court’s recent decision in the Padilla v. ICE case protects these immigrants’ right to a bond hearing. It is set to go into effect on July 16. It applies nationwide to people who enter the United States between ports of entry, are put into a fast-tracked deportation process called expedited removal, and then pass an initial screening interview about their requests for asylum. The government is likely to ask a higher court to overturn the decision.

In response to Tuesday’s decision, the White House issued a statement. The statement claims that the decision in Padilla would somehow “lead to the further overwhelming of our immigration system” and that amounted to the judge “[imposing] his or her open borders views on the country.”

Unfortunately, this is merely more of the same from the Trump administration. The White House regularly sends out harmful, anti-immigrant rhetoric with no basis in fact and attacks the courts when judges uphold the Constitution. In reality, Tuesday’s decision simply protects against the Attorney General’s unlawful efforts to upend a half century of standard immigration court procedure by indefinitely and unnecessarily incarcerating asylum seekers.

No one should be subject to arbitrary imprisonment while seeking asylum. This decision could protect many immigrants who would otherwise spend months or years locked up by the Department of Homeland Security simply because they are seeking protection in the United States.

Source: www.immigrationimpact.com

https://www.inmigracionyvisas.com/a4294-Asylum-Seekers-Must-Receive-a-Bond-Hearing-Within-7-Days.html

Etiquetas:

Asylum,

Asylum Seekers,

Detention,

Due Process & the Courts,

Humanitarian Protection,

immigration courts,

protect many immigrants

martes, 15 de enero de 2019

The Judicial Black Sites the Government Created to Speed Up Deportations

Written by Katie Shepherd

As the Trump administration continues to strip away due process in immigration courts, the recent creation of two “Immigration Adjudication Centers” is cause for concern. The two new facilities are called “Centers,” not “courts,” despite being places where judges decide whether to issue orders of deportation.

The Centers came out of a “ Caseload Reduction Plan” devised by the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) as one of several mechanisms designed to reduce the number of cases pending before the immigration courts. This initiative first surfaced in December 2017 ostensibly as one of a series of ways to address the record-high backlog within the immigration court system. In fact, EOIR’s caseload has almost tripled since 2011, from fewer than 300,000 pending cases to 810,000 as of November 2018. This is likely to worsen given the current government shutdown.

A total of fifteen Immigration Judges currently sit in the two Centers—four in Falls Church, Virginia, and 11 in Fort Worth, Texas.

It is unclear whether the Centers are open to the public, despite laws stating such hearings must be. All the cases heard by immigration judges in the Centers will be conducted exclusively by video-teleconference (VTC), with immigrants, their lawyers, and prosecutors in different locations.

According to one source , it’s likely that “thousands of immigration cases will be heard with respondents never seeing a judge face-to-face.”

The utter lack of transparency around these Centers is alarming, given the documented concerns with the use of video teleconferencing and the current administration’s commitment to speed up immigration court hearings, even at the risk of diminished due process.

Speeding up cases could benefit detained individuals who often languish for months or even years behind bars before their release or deportation. However, the impact of these Centers overall could be much more ominous.

The Centers raise serious questions about whether detained immigrants will be disadvantaged by the arrangement. These questions include:

- How will an individual who is unrepresented and detained in a facility three time zones away from the judge submit critical evidence to the court during a hearing?

- How can an immigration judge adequately observe an asylum seeker’s demeanor for credibility without being in the same room?

- Will the immigration judges be required to postpone hearings if there are issues with the telephonic interpreters, and could this lead to prolonged detention?

Further, only 14 percent of detained immigrants have attorneys and many may not have the ability to adequately prepare for their cases on an expedited timeframe. A very real outcome of speeding up cases in this manner is that many immigrants are deported even though they may have valid claims to stay in the United States.

Until the government is more transparent with these Centers, there is simply no way of knowing how many detained individuals—including children—have been deported without the opportunity to obtain counsel, and without appropriate safeguards preventing their removal to imminent harm.

Source: http://immigrationimpact.com/

http://www.inmigracionyvisas.com/a3992-the-government-Created-to-Speed-Up-Deportations.html

lunes, 13 de agosto de 2018

DHS To Restart Deportation Cases For Hundreds Of Thousands Of Immigrants

Written by Aaron Reichlin-Melnick

Recently released internal communications at Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) reveal a plan to restart the deportation cases of hundreds of thousands of people whose cases are currently administratively closed. This initiative has the potential to swell the immigration court backlog (currently at 730,000 cases) to over one million cases.

Administrative closure is a docket-management tool which allows immigration judges to temporarily take a case off of their docket. Immigration judges typically grant administrative closure to allow an immigrant to seek relief outside of immigration court or because ICE exercised prosecutorial discretion and decided not to move forward with a case. Once ICE or an immigrant in removal proceedings chooses to move forward with the case, they can ask the judge to “recalendar” the case by placing it back on the docket. .

When Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned decades of precedent in May 2018 by stripping immigration judges and the Board of Immigration Appeals of their general authority to administratively close cases, he left ICE with the decision to recalendar over 355,000 cases currently administratively closed. The newly-released instructions to ICE prosecutors reveal that ICE intends to recalendar virtually all of those cases. .

ICE prosecutors are instructed to prioritize recalendaring cases where the immigrant is detained, followed by all cases where the immigrant has a criminal record. Next, the agency will prioritize cases where ICE’s most recent motion to recalendar was denied, followed by those that administratively closed over ICE’s objections. Finally, it directs local offices to recalendar the remaining cases through a “case-by-case determination … considering available resources and the existing backlog in the local docket.” .

This last instruction has the potential to seriously limit the effect of ICE’s new policy. Because the agency’s resources are already strained by prosecuting new cases brought under the Trump administration, local ICE offices may not have the resources to recalendar many of the cases included in that last group. However, by indicating that the agency views virtually all 355,000 cases as legitimate targets for future enforcement, any immigrant whose case is currently administratively closed now faces an uncertain future. .

If fully implemented, ICE’s new guidance would have a significant effect on the tens of thousands of people who had their cases administratively closed from 2012 to 2016. Most cases administratively closed had benefited from a favorable exercise of prosecutorial discretion after the Obama administration determined that they were not an enforcement priority. Now, with the elimination of immigration enforcement priorities under the current administration, ICE may haul them back to immigration court again. .

ICE’s plan shows that the agency is eager to seek deportation of all who cross their path, regardless of whether they should be a priority for immigration enforcement or whether the agency will overwhelm the immigration court system in the process. In fact, an independent report commissioned by the immigration courts in 2017 recommended that more cases be administratively closed as an effective tool to reduce the backlog. .

The administration must make smarter use of its limited resources to ensure that enforcement does not needlessly harm countless people who pose no risk to public safety.

Source: www. immigrationimpact.com

http://www.inmigracionyvisas.com/a3871-DHS-To-Restart-Deportation-Cases-For-Of-Immigrants.html

jueves, 12 de julio de 2018

USCIS Is Slowly Being Morphed Into an Immigration Enforcement Agency

Written by Joshua Breisblatt

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) issued new guidance to initiate deportation proceedings for thousands of applicants denied for any immigration benefit. This policy change will have far-reaching implications for many of those interacting with the agency, but also signals a major shift in how USCIS operates.

USCIS was never meant to be tasked with immigration enforcement. Their mandate has always been administering immigration benefits. With its distinct mission, USCIS was created to focus exclusively on their customer service function , processing applications for visas, green cards, naturalization, and humanitarian benefits.

The new USCIS guidance instructs staff to issue a Notice to Appear (NTA) to anyone who is unlawfully present when an application, petition, or benefit request is denied. This will include virtually all undocumented applicants, as well as those individuals whose lawful status expires while their request is pending before USCIS.

An NTA (Form I-862) is a charging document issued to individuals when there are grounds for deporting them from the United States. The NTA is issued by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and USCIS. It must be served to the individual and presented to the immigration court for removal proceedings to be triggered. When someone receives an NTA, they must appear before an immigration judge at an assigned date and location to determine if they are eligible to remain in the country legally or should be removed.

NTAs are traditionally issued under certain situations, such as terminations of conditional permanent residence, referrals of asylum cases, and positive credible fear findings.

Beginning immediately, NTAs will also be issued by USCIS:

- For denials of an initial application or re-registration for Temporary Protected Status (TPS) or a withdrawal of TPS when the applicant has no other lawful immigration status.

- When fraud, misrepresentation, or evidence of abuse of public benefit programs is part of an individual’s record, even if the application or petition has been denied for other reasons.

- When someone is under investigation or arrested for any crime, regardless of a conviction, if the application is denied and the person is removable.

- When USCIS issues an unfavorable decision and the individual is not lawfully present in the United States.

A second policy memorandum issued at the same time as the new NTA guidance makes applicants for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) the exception to this new NTA policy.

This move essentially ends all prosecutorial discretion, a key tool used by law enforcement and prosecutors all over the country to effectively prioritize cases. In the past, immigration agencies used prosecutorial discretion when deciding under what circumstances to issue NTAs.

Past leaders of USCIS have issued memos against the practice of widespread NTA issuance, noting it was impractical, would divert scarce resources, create longer wait times, and clog the immigration courts. Further, denials of immigration benefits applications are often reversed upon reconsideration or appeal. This means that thousands of cases that will ultimately be approved will be needlessly tossed onto the dockets of an already overburdened court system. If an immigration benefit request is approved on appeal, the individual must then seek termination of proceedings, which consumes even more court resources. With over 700,000 cases already in the court backlog , it’s inconceivable for the agency to manage many thousands more.

This new NTA policy is both overbroad and short-sighted, not taking into account the practical effects on government resources or the chilling effect it will have on noncitizens needing to apply for or renew benefits. Our complex immigration system will become even more inefficient, burdensome, and confusing.

Source: www. immigrationimpact.com

http://inmigracionyvisas.com/a3846-USCIS-Into-an-Immigration-Enforcement-Agency.html

Etiquetas:

Adjustment of Status,

Benefits & Relief,

Donald Trump,

featured,

immigration backlog,

immigration courts,

Reform,

USCIS

lunes, 13 de marzo de 2017

The Sad State of Atlanta’s Immigration Court

Written by Hilda Bonilla MARCH 10, 2017 in Immigration Courts

The Atlanta immigration court is known as one of the worst places to be in deportation proceedings. For years, the judges have been accused of abusive and unprofessional practices and the denial rate of asylum applications alone is 98 percent.

The latest effort to document this phenomenon comes from Emory Law School and the Southern Poverty Law Center who sent a letter to the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) this month regarding troubling practices in the Atlanta immigration courts. The letter was based on court observations by Emory Law students, who attended 31 proceedings between August 31 and October 14, 2016.

Observers found that the immigration judges made prejudicial statements, demonstrated a lack of courtesy and professionalism and expressed significant disinterest toward respondents. In one hearing, an attorney argued that his client should be released from detention because he was neither a threat to society nor a flight risk. In rejecting the client’s bond request, the immigration judge reportedly compared an immigrant to a “person coming to your home in a Halloween mask, waving a knife dripping with blood” and asked the attorney if he would let him in.

When the attorney disagreed with this comparison, the immigration judge responded that the “individuals before [him] were economic migrants and that they do not pay taxes.” Another immigration judge reportedly “leaned back in his chair, placed his head in his hands, and closed his eyes” for 23 minutes while the respondent described the murder of her parents and siblings during an asylum hearing.

Other critical problems include disregard for legal arguments, frequent cancellation of hearings at the last minute, lack of individualized consideration of bond requests, and inadequate interpretation services for respondents who do not speak English. The observers also reported that immigration judges often refer to detention centers as “jails” and detainees as “prisoners,” undermining their dignity and humanity and suggesting that the IJs perceive detained immigrants as criminals. Compounding this problem, detained immigrants who appear in immigration court in Atlanta are required to wear jumpsuits and shackles.

Many of these practices stand in stark contrast with the Executive Office of Immigration Reviews’ Ethics and Professionalism Guide for Immigration Judges, which state, among other things, that “an immigration judge… should not, in the performance of official duties, by word or conduct, manifest improper bias or prejudice” and that immigration judge should be “patient, dignified, and courteous, and should act in a professional manner towards all litigants, witnesses, lawyers, and other with whom the immigration judge deals in his or her capacity.”

EOIR has been previously criticized for its lack of transparency on providing the public with information about the complaints brought up against immigration Judges, raising questions about the department’s willingness to hold its judges accountable. For these reasons, the American Immigration Lawyers Association submitted a Freedom of Information Act request on December 2016 requesting records on all complaints filed against immigration judges and how the complaints were resolved. The released records showed that many immigration judges have been accused of abusive behavior towards immigrants.

The letter concludes with recommendations that, if implemented, have the potential to significantly improve the fairness of immigration court proceedings in one of the most hostile jurisdictions in the country. These recommendations include: investigating and monitoring immigration judges at the Atlanta immigration court, requiring immigration judges to record all courtroom proceedings to ensure transparency and accountability for prejudicial statements, investigating the frequent cancellation of hearings, and ensuring high-quality interpretation and availability of sample translations of forms. It is time for EOIR to take these recommendations seriously.

Photo by Tim Evanson.

Source: http://immigrationimpact.com

http://inmigracionyvisas.com/a3560-Atlanta-Immigration-Court.html

Etiquetas:

Atlanta,

deportation,

Emory Law School,

EOIR,

featured,

Georgia,

immigration courts,

immigration judges,

lawyers,

litigants,

Southern Poverty Law Center,

witnesses

Suscribirse a:

Entradas (Atom)