Created in 1996, expedited removal is a process by which low-level immigration officers can quickly deport certain noncitizens who are undocumented or have committed fraud or misrepresentation. Since 2004, immigration officials have used expedited removal to deport individuals who arrive at our border, as well as individuals who entered without authorization if they are apprehended within two weeks of arrival and within 100 miles of the Canadian or Mexican border.

On January 25, 2017, President Trump issued an executive order which directed the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to dramatically expand the use of “expedited removal” to its full statutory extent. n July 22, 2019, the Department of Homeland Security announced that it would carry out the full expansion. As of July 23, 2019, expedited removal may be applied to individuals who are undocumented, or who have committed fraud or misrepresentation, and who are encountered within the entire United States and who have not been physically present in the United States for two years prior to apprehension.

One of the major problems with expedited removal is that the immigration officer making the decision virtually has unchecked authority. When an immigration official encounters someone they believe may be subject to expedited removal, the burden of proof is on the individual to prove otherwise. This means that an individual believed to be subject to expedited removal will have the burden of proving to an immigration official that they have been physically present in the United States for two or more years or that they were legally admitted or paroled into the United States.

Individuals subject to expedited removal rarely see the inside of a courtroom because they are not afforded a regular immigration court hearing before a judge. In essence, the immigration officer serves both as prosecutor and judge. Further, given the speed at which the process takes place, there is rarely an opportunity to collect evidence or consult with an attorney, family member, or friend before the decision is made.

Such a truncated process means there is a greater chance that persons are being erroneously deported from the United States, potentially to imminent harm or death. Moreover, individuals who otherwise might qualify for deportation relief if they could defend themselves in immigration court are unjustly deprived of any opportunity to do so. Yet expedited removal has been increasingly applied in recent years; 35 percent of all removals from the United States were conducted through expedited removal in Fiscal Year (FY) 2017, the most recent government data available. A dramatic expansion, as directed by President Trump and implemented In July 2019, could result in thousands of additional deportations without due process.

What the Law Says

“Expedited removal” refers to the legal authority given to even low-level immigration officers to order the deportation of some non-U.S. citizens without any of the due-process protections granted to most other people—such as the right to an attorney and to a hearing before a judge. The Illegal Immigration and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 created expedited removal, but the federal government subsequently expanded it significantly.

As it now stands, immigration officers can summarily order the removal of nearly any foreign national who arrives at the border without proper documents; additionally, undocumented immigrants who have been in the United States 14 days or less since entering without inspection are subject to expedited removal if an immigration officer encounters them within 100 miles of the U.S. border with either Mexico or Canada. As a general rule, however, DHS applies expedited removal to only those Mexican and Canadian nationals with histories of criminal or immigration violations, as well as persons from other countries who are transiting through Mexico or Canada. There is no right to appeal an immigration officer’s decision to deport someone via expedited removal. Individuals in expedited removal are detained until removed.

By law, expedited removal may not be applied to certain individuals. U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents (LPRs, or “green card” holders) should not be subject to expedited removal. Nor should it be used against refugees, asylees, or asylum seekers (people who fear persecution in their home countries or indicate an intention to apply for asylum).

Asylum seekers are instead referred to an asylum officer for an interview to determine if they have a “credible fear” of persecution. If an individual has been previously deported, an asylum officer determines if the person has a “reasonable fear” of persecution—a higher standard than “credible fear.” If the asylum officer fails to find that the person has a credible or reasonable fear of return, that person is ordered removed. Before deportation, the individual may challenge the asylum officer’s adverse finding by requesting a hearing before an immigration judge, who must review the case “to the maximum extent practicable within 24 hours, but in no case later than 7 days….” The judge’s review is limited solely to assessing whether the individual’s fear is credible or reasonable.

Individuals found to have a credible or reasonable fear of persecution are detained pending further review of their asylum case. In limited circumstances, these individuals may be paroled—that is, released from detention—and permitted to remain in the United States while their asylum case is pending.

Until January 2017, an exception to expedited removal had been made for “an alien who is a native or citizen of a country in the Western Hemisphere with whose government the United States does not have full diplomatic relations and who arrives by aircraft at a port of entry.” Cubans arriving by aircraft had been exempted from expedited removal under this provision, but in the closing days of the Obama administration, DHS published a regulation eliminating Cuban nationals from the exemption

Use of Expedited Removal Is on the Rise

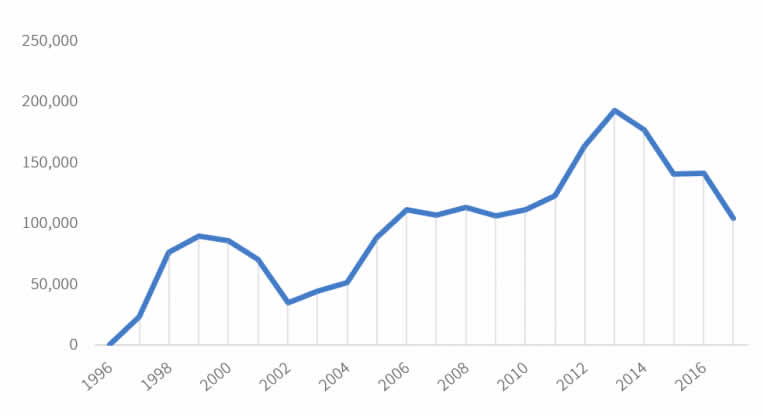

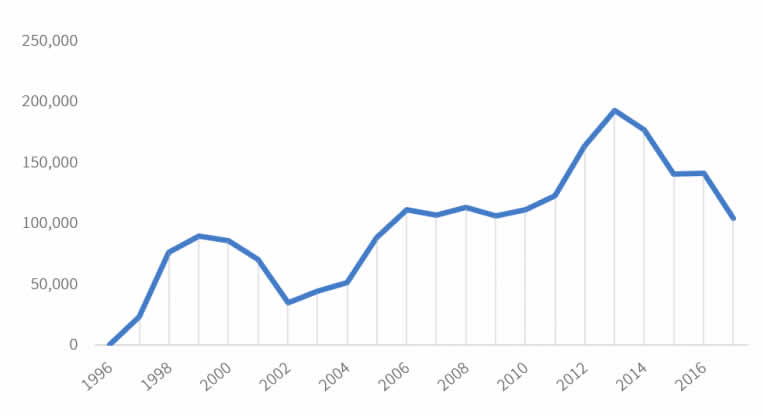

The use of expedited removal to deport people has risen substantially over the past two decades, peaking in FY 2013 when approximately 193,000 persons were deported from the United States through expedited removal, which represented 43 percent of the 438,000 removals from the United States that year. After 2013, the number of people deported from the United States through expedited removal fell, likely as a result of more asylum seekers who were found to have a credible fear of persecution. However, expedited removal still accounted for 35 percent of all deportations in FY2017.

Fig. 1 Expedited Removals FY 2001-2017

Source: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Immigration Enforcement Actions: 2010-2017; U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, 2000 Statistical Yearbook, chp. 6.

Concerns about Expedited Removal

Erroneous Deportations

There are few checks on the authority of immigration officers to place non-citizens in expedited removal proceedings. In essence, the law permits the immigration officer to serve both as prosecutor (charged with enforcing the law) and judge (rendering a final decision on the case). Generally, the entire process consists of an interview with the inspecting officer, so there is little or no opportunity to consult with an attorney or to gather any evidence that might prevent deportation. For those who are traumatized from their journey or harm they fled, the short timelines can make it extremely difficult to clearly explain why they need protection in the United States. The abbreviated process increases the likelihood that a person who is not supposed to be subject to expedited removal—such as a U.S. citizen or LPR—will be erroneously removed. Moreover, individuals who otherwise would be eligible to make a claim for “relief from removal” (to argue they should be permitted to stay in the United States) may be unjustly deprived of any opportunity to pursue relief. For example, a witness or victim of a crime might be eligible for status but is prohibited from making such a claim in expedited removal proceedings.

Inadequate Protection of Asylum Seekers

In practice, not all persons expressing a fear of persecution if returned to their home countries are provided a credible or reasonable fear screening. Studies by the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) noted that, in some cases, immigration officers pressured individuals expressing fear into withdrawing their application for admission—and thus their request for asylum—despite DHS policies forbidding the practice. In other cases, government officers failed to ask if the arriving individual feared return. In addition, the Commission found that the government did not have sufficient quality assurance mechanisms in place to ensure that asylum seekers were not improperly being turned back.

A Growing Backlog of Asylum Applications

Individuals expressing fear of return who are diverted from expedited removal are referred to asylum officers for screening. These officers are often the same corps handling affirmative asylum applications (i.e., cases filed by individuals not in removal proceedings). Since these asylum seekers are detained pending completion of the credible or reasonable fear process, their cases are prioritized by the government. Asylum Office resources are therefore diverted to these interviews, contributing to the backlog of affirmative asylum cases.

Further expansion of expedited removal will require significantly more asylum officers, or the backlog of affirmative asylum cases will continue to grow. This workload management crisis could be avoided entirely if DHS personnel placed all asylum seekers apprehended at the border in regular immigration court proceedings and paroled them pending their hearings. Providing the immigration court system with enough funds to sufficiently staff immigration judge teams would help ensure that asylum seekers get a prompt court hearing.